Horn

How many times have you gone to a concert hall, or tuned in to your local classical music radio station, to listen to a work by Bach, Brahms, or Beethoven? Or Borodin, Bizet, Britten, Berlioz, Bellini, or Bruckner? But have you ever heard of Bridgetower, Bonds, or Beach? The world of classical music has a long way to go when it comes to diversifying its administrations, ensembles, and audiences, but also its repertoire, which is full to the brim with incredible composers that are under-appreciated and under-programmed. The call for a racial reckoning in classical music that has gained momentum after the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, and the ample amount of free time with which COVID-19 has provided me, led me to create this project.

Alphabet of Composers is dedicated to telling the stories of 26 composers of diverse backgrounds that have been left out of the traditional western classical 'canon' because of their race, gender, or both. I hope that you enjoy reading these as much as I enjoyed writing them, and that you remember their names.

A is for: Yasushi Akutagawa

There are many composers who were well-known, even famous in their day, but have since fallen out of the public eye. One such composer is Yasushi Akutagawa, whose symphonies, orchestras, ballets, and film scores were a sensation in his native Japan, and charmed audiences across the globe. Born in Tokyo, Akutagawa (1925-1989) was the son of the famous writer Ryunosuke Akutagawa. He studied under leading Japanese composers Akira Ifukube and Kunihiko Hashimoto, but was also strongly influenced by Soviet composers, including Shostakovich and Khachaturian, with whom he became friends in the 1950s.

After World War Two, and during the ever-growing tensions of the Cold War, Akutagawa became a major figure in the musical and cultural exchange between Japan and the Soviet Union. Before diplomatic relations between the two governments were re-established in 1956, he traveled illegally to the Soviet Union, and was the only Japanese composer whose works were officially published there during that time period.

Yasushi Akutagawa

Akutagawa’s music also played a role in goodwill relations between Japan and the United States. His lively two-movement work Music for Symphony Orchestra (1950) was premiered in Tokyo by the NHK Symphony Orchestra and became immediately popular in Japan. In 1955, American conductor Thor Johnson and the Symphony of the Air (formerly Toscanini’s NBC Symphony Orchestra) performed Music for Symphony Orchestra on a goodwill tour to Japan sponsored by the US State Department. The performances were hugely popular, and Johnson was quoted as saying “I have long desired to play a Japanese composition, and now am very glad to say that dream came true.” After the tour Johnson programmed Music for Symphony Orchestra on performances and broadcasts across the United States, leading to its widespread recognition.

One of Akutagawa’s most popular pieces is a work for string orchestra called Triptyque. In three movements, Allegro, Berceuse, and Presto, this exciting work is playful in its use of dissonance and masterful in its command of string textures. The first movement, with its driving rhythms and unrelenting pulse, reminds me particularly of Shostakovich’s String Quartets (No. 8, Allegro molto) or Symphonies (No. 5, about halfway through the first movement.)

Akutagawa wrote only one opera, Orpheus in Hiroshima (1960) which became well-known in the West when a 1967 version for TV film was broadcast across the US. In only one 45-minute act, the gripping libretto by Kenzaburō Ōe tells of a young man (baritone) disfigured by the atomic blast. A mysterious woman (contralto) gives him a dark mirror which pulls him into a parallel world. In this mirror land he falls in love with a beautiful girl (soprano), and decides he must surgically correct his disfigurement in order for them to be happy. In a cruel twist, the girl turns out to be a messenger of death, but just as a chauffeur (tenor) is about to drive him into the underworld, the girl gives him one final chance. Our hero awakes in the real world and goes to the hospital to undergo the dangerous surgery, only to find that the nurse is his beloved, and the surgeon is the chauffeur. The opera comes to a dramatic end just as the surgeon raises the scalpel, leaving the audience to wonder at his fate.

Akutagawa also composed numerous film scores, including Teinosuke Kinugasa's Gate of Hell (1953) and Kon Ichikawa's Fires on the Plain (1959). Dedicated to music education, he established an award-winning amateur orchestra, Shin Kokyo Gakudan (The New Symphony Orchestra), and after his death the Suntory Foundation established the Akutagawa Award for Music Composition.

Listening:

Music for Symphony Orchestra:

B is for: Margaret Bonds

Margaret Bonds was one of the first Black women composers who broke through racist and sexist barriers in western classical music, but she has not received the level of acclaim and recognition she has long been due. Born and raised in Chicago, Margaret Bonds (1913-1972) came of age during the Great Migration and the cultural renaissance it brought. She began studying piano with her mother when she was very young, and before she had finished school she went on to study with composers Florence Price and William Dawson. She was admitted to Northwestern University in 1929, but because of her race she was barred from living on campus or using their facilities. Bonds persevered despite all the horrific prejudice she faced at the school, and won the prestigious Wanamaker Award in her third year for her piece Sea Ghost.

Margaret Bonds

In 1933 she performed Florence Price’s Piano Concerto with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, becoming the first Black soloist to perform with any major American orchestra, and a year later graduated Northwestern with a bachelor’s and master’s degree in music. She moved to New York City in 1939 and become a major figure in the Harlem Renaissance and a devoted civil rights activist, alongside poet Langston Hughes, who went on to be her life-long friend and creative partner.

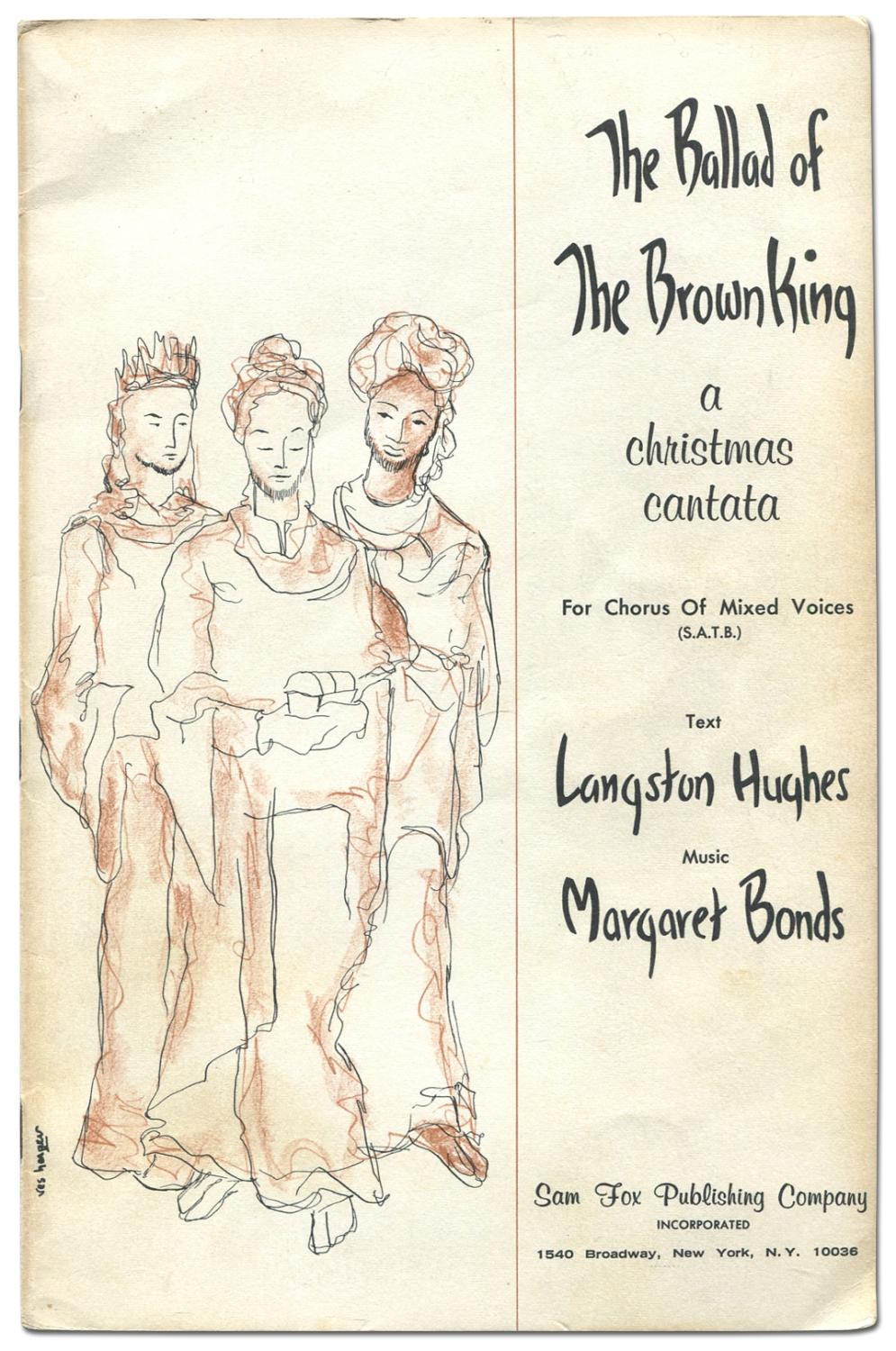

One of Bonds’ most celebrated works is a Christmas cantata, The Ballad of the Brown King, which was premiered in New York in 1954. Written for soprano, tenor, baritone, and choir, and re-scored in 1960 to include a full orchestra, the nine movement work is a rich tapestry woven of European, jazz, calypso, and African spiritual influences. The text, written by Langston Hughes, tells the story of the birth of Jesus from the perspective of the African king, Balthazar, and is dedicated to Martin Luther King Jr. The full orchestra version was broadcast by CBS on Christmas Day 1960, and following its widespread popularity Bonds received many commission requests, including from acclaimed opera singers Leontyne Price and Betty Allen.

Words and lyrics to The Ballad of the Brown King: A Christmas Cantata, 1961, from the Langston Hughes Papers at Yale University

Bonds wrote many other works with text by Hughes, including a setting of The Negro Speaks of Rivers for voice and piano, which was premiered by Etta Moten (for whom the role of Bess in Porgy and Bess was written.) One of her most famous works is Three Dream Portraits, a short and moving setting for voice and piano of three Hughes poems, Minstrel Man, Dream Variations, and I, Too. The last movement, I, Too, is especially poignant, with the text reflecting on the identity and experience of Black people in America, who are systematically marginalized and oppressed to this day. Malcolm J Merriweather, the baritone on the recording linked below, says “When I sing 'Dream Variation' I feel the weight of my ancestors on my shoulders through the harmonies and textures. In Bonds, I see my aunts, grandmothers and even my own mother - strong, capable women who at one point or another were undervalued and stifled by white supremacy in America. That sense of struggle is not merely expressed but it screams to me. It is all packaged neatly in the form of an art-song.”

Listening:

Ballad of the Brown King and Three Dream Portraits:

C is for: Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

Have you heard of the English Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge? What about the trail-blazing Anglo-African composer, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor?

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912), who was named after the poet, was extremely popular in the early 20th Century but has since fallen into relative obscurity. Coleridge-Taylor was of mixed race and was raised by his English mother and grandfather in Croydon. His father was a doctor from Sierra Leone, who returned to his home country soon after his son’s birth after being unable to practice medicine in London because “patients did not trust a Black doctor working without white supervision.” His early musical education came from his grandfather, who taught him to play the violin, and a choirmaster at the local Anglican church where he was a choirboy.

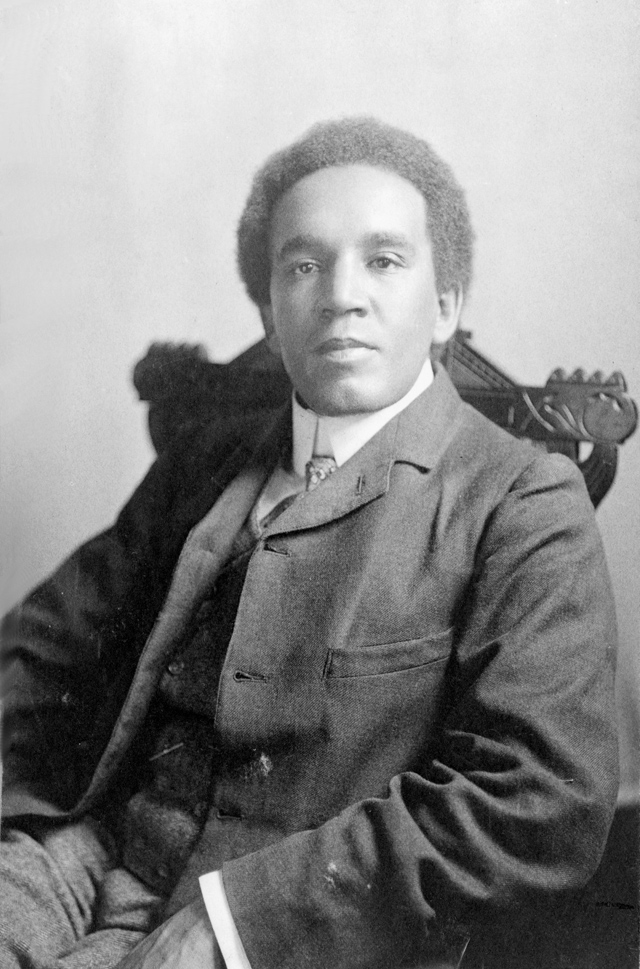

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, 1905

Coleridge-Taylor began studying violin and later composition at the Royal College of Music in 1890 at the age of 15, one of the first Black students to gain admission to the school. His teacher was the well-known Irish composer Charles Villiers Stanford, and two of his fellow students were Ralph Vaughan Williams and Gustav Holst, who he outshined. Soon after graduating he became a professor at Crystal Palace School of Music, and a conductor at the Croydon Conservatoire. In 1896 Edward Elgar recommended him for the Three Choirs Festival, describing him as “far and away the cleverest fellow going amongst the younger men.” The Festival commissioned Coleridge-Taylor to write Ballade for Orchestra, which was one of his first major successes.

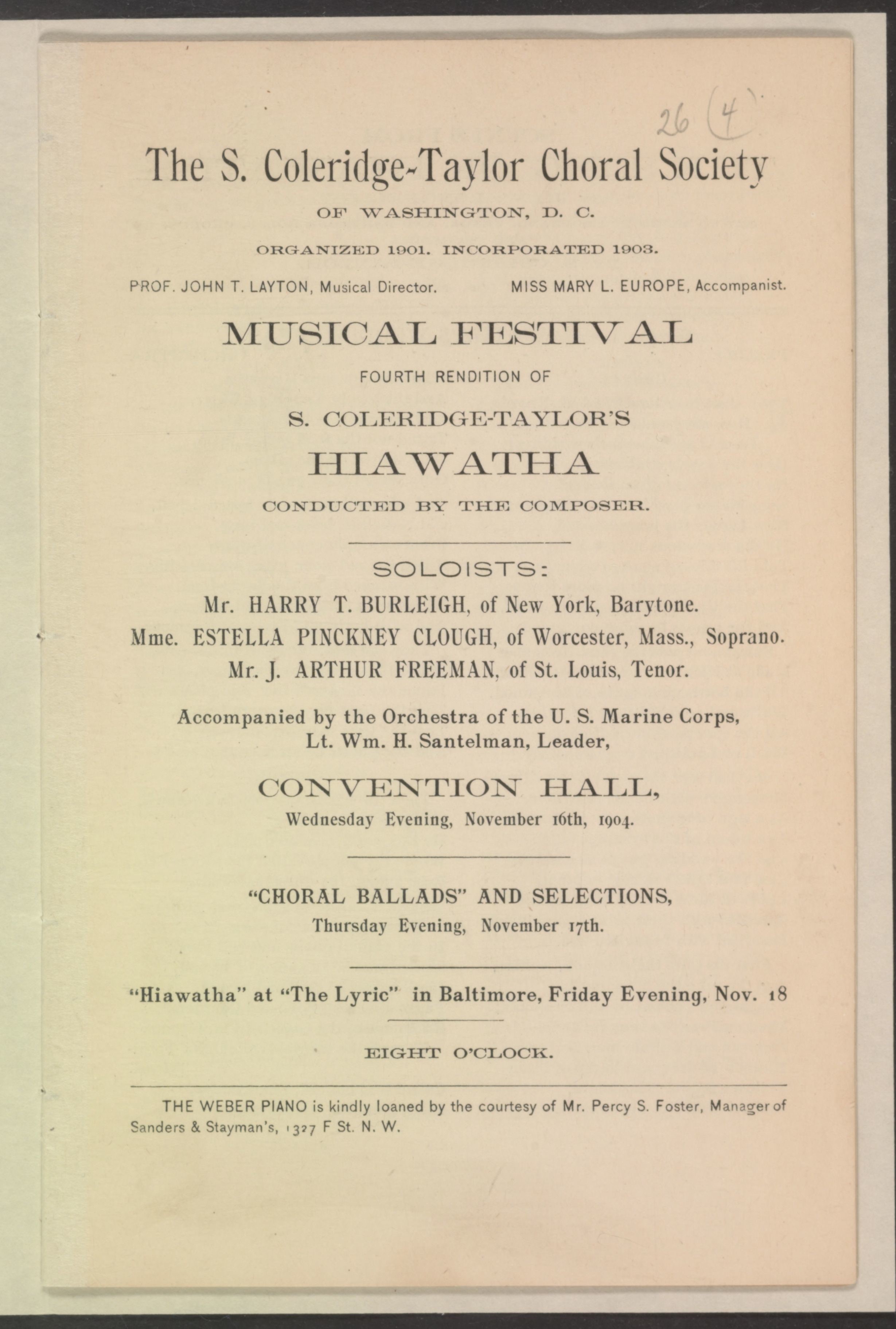

Coleridge-Taylor’s most famous piece is undoubtedly Scenes from The Song of Hiawatha (1898-1900), a trilogy of cantatas based on the epic poem of the same name by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, which tells the story of a Native American hero named Hiawatha and his love Minnehaha. Although the work is comprised of an overture and three movements, Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast, The Death of Minnehaha, and Hiawatha’s Departure, the first movement in particular became so popular that it was performed by choral societies across England hundreds of times in the early 1900s. The work was such a sensation that it garnered a huge amount of international attention, and Coleridge-Taylor led performances of it on three tours of the United States in 1904, 1906, and 1910, becoming the first man of African descent to conduct a white orchestra in the US. His 1904 tour was sponsored by the Coleridge-Taylor Choral Society, a 200-member African American choir in Washington DC dedicated to performing his works. With Coleridge-Taylor at the podium, they performed The Song of Hiawatha with the Orchestra of the US Marine Corps, and the composer was invited to visit President Theodore Roosevelt at the White House.

Program pamphlet from 1904 tour, Convention Hall, Wednesday, November 16,1904

At the end of the story of Hiawatha, white missionaries convert the Ojibwe tribe to Christianity. Coleridge-Taylor drew a parallel between the religious conversion of the Native American people and that of the native populations of Sierra Leone and other African British Colonies. In the Overture, he makes this connection clear by using the African American spiritual Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen as the basis for the theme.

Coleridge-Taylor drew from African American spirituals in many of his other pieces as well, notably in Twenty-Four Negro Melodies (1905) for solo piano, which became immensely popular. In the introduction, Coleridge-Taylor says, “What Brahms has done for the Hungarian folk-music, Dvořák for the Bohemian, and Grieg for the Norwegian, I have tried to do for Negro melodies.”

Outside of his work in composition, Coleridge-Taylor was an outspoken advocate for Pan-Africanism, serving as a delegate to the world’s first Pan-Africanist conference in 1900, where he became friends with fellow activist W.E.B. Du Bois. He married pianist Jessie Walmisley in 1899, and they had a son, Hiawatha, and a daughter, Gwendolen 'Avril.' When Coleridge-Taylor died from pneumonia at the young age of 37, he held positions at the Croydon Conservatoire, Trinity College of Music, Crystal Palace School of Art and Music, Guildhall School of Music, and the London Handel Society.

Scholar Jeffrey Green writes of Coleridge-Taylor’s legacy: “By including African, Afro-American, and Afro-Caribbean elements in his compositions in melody and in title, as well as by being visibly and proudly of African descent, the music and the achievements of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor had made Black concert musicians proud and able to walk tall.”

Listening:

Ballade for Orchestra, performed by the Chineke! Orchestra:

24 Negro Melodies, performed by Frances Walker:

Scenes from the Song of Hiawatha, performed by the Philharmonia Orchestra and the Royal Choral Society, with Richard Lewis, tenor:

My thanks and appreciation to Southbank Sinfonia for supporting this project, and to Sam Olivier for his gracious help in editing. Where I have quoted or used information from other people and publications, those sources can be found in the references.

Find out more about Antonia here

Check out a playlist of listening recommendations here:

Read 'Alphabet of Composers: D, E, and F' here

Read 'Alphabet of Composers: G, H, and I' here

References:

Amacher, Julie, et al. “Hear a Retelling of the Nativity Story in Margaret Bonds' 'The Ballad of the Brown King'.” New Classical Tracks, Classical MPR, 25 Dec. 2019, www.classicalmpr.org/story/2019/12/25/new-classical-tracks-ballad-of-the-brown-king. Accessed 20 July 2020.

Burrage, Hilary. “Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912), Britain's Foremost Black Classical Composer: The Centenary Legacy.” HuffingtonPost.co.uk, Huffington Post, 29 Aug. 2012, www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/hilary-burrage/samuel-coleridgetaylor-18_b_1834759.html.

Coleridge-Taylor, Samuel, et al. Scenes from The song of Hiawatha. [Washington, D.C.?: s.n, 1904] Pdf. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/91898526/>.

Green, Jeffrey P. Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, a Musical Life. Routledge, 2016.

Cabrera, Donato. “The Music Plays on - Samuel Coleridge-Taylor.” Medium, Medium, 5 June 2020, medium.com/@donatocabrera/the-music-plays-on-samuel-coleridge-taylor-d70e8a8d2771.

Eder, Bruce. “Yasushi Akutagawa: Biography & History.” AllMusic, www.allmusic.com/artist/yasushi-akutagawa-mn0001653550/biography.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Samuel Coleridge-Taylor.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 28 Aug. 2019, www.britannica.com/biography/Samuel-Coleridge-Taylor.

Ericson, Raymond. Review of TV: Two Filmed Operas, Review of NET Opera Theater Series, 1971 The New York Times, 1 Feb. 1971, p. 63, timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1971/02/01/81873380.html?pageNumber=

“Intimate Circles: Margaret Bonds.” Intimate Circles: American Women in the Arts | Margaret Bonds, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, July 2003, brbl-archive.library.yale.edu/exhibitions/awia/gallery/bonds.html.

“Japanese Orchestral Favorites.” NaxosDirect, naxosdirect.co.uk/items/japanese-orchestral-favourites-145881.

Jones, Randye. “Margaret Bonds Biography.” Afrocentric Voices in "Classical" Music, 13 Dec. 2019, afrovoices.com/margaret-bonds-biography/.

Kanazawa, Masakata. “Hiroshima No Orufe ('Orpheus in Hiroshima').” Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online, doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.O902125.

“Margaret Bonds and Langston Hughes: A Musical Friendship.” Edited by Celenza Anna, Georgetown University Library, Georgetown University Library, 30 Aug. 2016, www.library.georgetown.edu/exhibition/margaret-bonds-and-langston-hughes-musical-friendship.

“Margaret Bonds.” Cedille Records, 14 Jan. 2020, www.cedillerecords.org/artists/margaret-bonds/.

“Margaret Bonds: A Unique Voice Crafted in the 20th Century.” Classical Music Indy, 19 Mar. 2018, www.classicalmusicindy.org/margaret-bonds-a-unique-voice-crafted-in-the-20th-century/.

“MARGARET BONDS: The Ballad of the Brown King & Selected Songs.” New Music USA, 15 Feb. 2020, www.newmusicusa.org/projects/margaret-bonds-the-ballad-of-the-brown-king-selected-songs/.

Revill, George. “Hiawatha and Pan-Africanism: Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912), a Black Composer in Suburban London.” Ecumene, vol. 2, no. 3, 1995, pp. 247–266. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44251770. Accessed 22 July 2020.

Salazar, David. “Composer Profile: Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Creator of 'The Song of Hiawatha' & 'Thelma'.” Opera Wire, 13 June 2020, operawire.com/composer-profile-samuel-coleridge-taylor-creator-of-the-song-of-hiawatha-thelma/.

“Samuel Coleridge-Taylor.” 100 Great Black Britons, Every Generation Media and Foundation, 100greatblackbritons.com/bios/samuel_coleridge-taylor.html.

“Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and the Musical Fight for Civil Rights - Royal College of Music - Google Arts & Culture.” Edited by Gabriele Rossi Rognoni et al., Google Arts and Culture, Google, artsandculture.google.com/exhibit/samuel-coleridge-taylor-and-the-musical-fight-for-civil-rights/JwLitwiLW6SGIw.

Shchedrin, Rodion. Rodion Shchedrin: Autobiographical Memories. Schott, 2013.

Smith, David, et al. “Margaret Bonds's The Ballad of the Brown King.” Presto Classical, 18 Nov. 2019, www.prestomusic.com/classical/articles/2984--interview-margaret-bondss-the-ballad-of-the-brown-king. Accessed 20 July 2020.

Thomas, William Ethaniel. Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Cambridge Chorus, cambridgechorus.org/docs/comps/SC-Taylor.html.

United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on Appropriations. The Supplemental Appropriation Bill, 1956: Hearings Before the Committee on Appropriations, United States Senate, Eighty-Fourth Congress, First Session, on H.R. 7278, an Act Making Supplemental Appropriations for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1956, and for Other Purposes Issue 1116 of Report, United States Congress. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1955, Google Books, books.google.co.uk/books?id=DME2k-aaNC4C&pg=PP5#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Zick, William J. “AfriClassical.com: Parents and Early Years of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, From Biography by Jeffrey Green.” AfriClassical.com, 28 Apr. 2012, africlassical.blogspot.com/2012/04/africlassicalcom-parents-and-early_28.html.

Zick, William J. “Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912).” Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Afro-British Composer & Conductor, AfriClassical.com, chevalierdesaintgeorges.homestead.com/Song.html.