Horn

The world of classical music has a long way to go when it comes to diversifying its administrations, ensembles, and audiences, but also its repertoire, which is full to the brim with incredible composers that are under-appreciated and under-programmed. Alphabet of Composers is dedicated to telling the stories of 26 composers of diverse backgrounds that have been left out of the traditional western classical 'canon' because of their race, gender, or both. I hope that you enjoy reading these as much as I enjoyed writing them, and that you remember their names.

D is for: William L. Dawson

William L. Dawson (1899-1990) was once described as ''the ancient voice of Africa transferred to America.'' His arrangements of African American spirituals are often performed in choirs and churches across the US, but his other works have been largely forgotten. Born in Anniston, Alabama, Dawson ran away from home at the age of 13 to go to school at the Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University) in order to receive a formal education. When he graduated with highest honors from the high school division in 1921, he had played in the band and orchestra, studied composition, toured with the choir, and could play almost any instrument. He went on to study theory and counterpoint at the Horner Institute of Fine Arts in Kansas City, Missouri, where he graduated in 1925 with a bachelor of music, but was barred from walking onstage to receive his diploma because of his race.

Dawson’s 1934 work Negro Folk Symphony was premiered by Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Symphony Orchestra. In three movements, 'The Bond of Africa,' 'Hope in the Night,' and 'O, le’ me shine, shine like a Morning star!,' Negro Folk Symphony is full of the lush harmonies and soaring melodies of the late-romantic era, but Dawson said he wanted anyone who listened to the piece to know that it was “unmistakably not the work of a white man.”

The heart-wrenching second movement opens with a gong and an English horn melody, accompanied by pizzicato strings and a plodding beat. In the program notes, Dawson said it has the “atmosphere of the humdrum life of a people whose bodies were baked by the sun and lashed with the whip for 250 years: whose lives were proscribed before they were born.” In 1952, Dawson traveled to seven different countries in West Africa in order to study the music indigenous to those regions, prompting him to revise Negro Folk Symphony with a more authentically African rhythmic foundation.

Negro Folk Symphony was raved about by audiences and the press alike, with one New York critic saying it was “the most distinctive and promising American symphonic proclamation which has so far been achieved.” Despite its critical and popular success, it was performed only a handful of times after the premiere and has since fallen into undeserved obscurity.

After retiring from Tuskegee, Dawson became a guest conductor with the Kansas City Philharmonic, the Nashville Symphony Orchestra, and the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, and he was inducted into the Alabama Arts Hall of Fame in 1975. Historian John Lovell said of Dawson’s legacy, “No one has made a stronger contribution to the presentation and understanding of the Afro-American folk song."

Listening:

Negro Folk Symphony, with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Neeme Järvi:

E is for: Manuel Enríquez

Throughout his prolific career spanning four decades, Mexican composer Manuel Enríquez (1926-1994) was not a one-note wonder. As one of the most influential Mexican composers of the 20th century, he composed over 150 works in a wide variety of styles, experimenting with serialism, nationalism, graphic scores, electronic music, and aleatoric music.

Enríquez was born into a musical family in Ocotlán, Jalisco, and began learning the violin with his father from an early age. He won a scholarship to attend the Juilliard School in New York City, where he earned Master’s degrees in violin and chamber music and found his passion for composition. After graduating he returned to Mexico and became a sought-after violinist, but continued composing. In 1971 he won the prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship and returned to the US to attend the Center of Electronic Music at Columbia University, where he started experimenting with electro-acoustical music.

Enríquez’ reach and inspirations were not only North American. He toured the United States, Europe, and the USSR with a string quartet he founded called the Mexico Quartet. In the 1970s he attended Darmstadt, the famous German summer academy of contemporary music, where he met fellow composers Luciano Berio, Iannis Xenakis, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Krzysztof Penderecki, and György Ligeti. Commissioned by the Mexican government to promote Mexican music in Europe, he lived in Paris from 1975-1977.

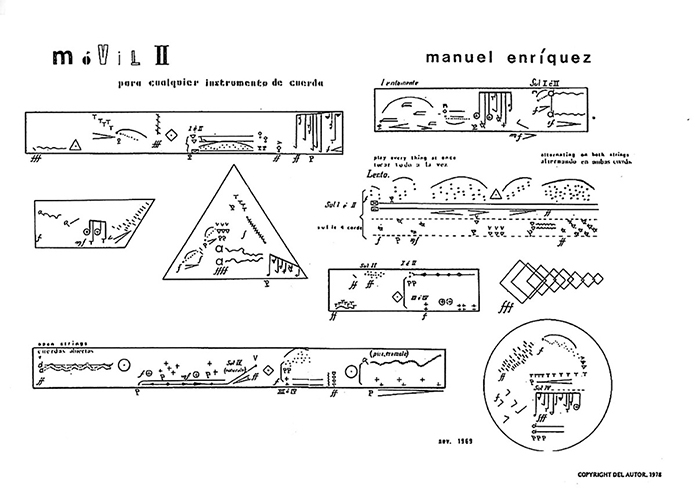

Enríquez composed in such a wide variety of styles that is difficult to give a representational example of his compositions. My favorite of his works is Suite para Violín y Piano (1963) which is in six short movements, each with a distinct character. It is one of his more traditional works, using folk-like themes and standard tuning and instrumentation, but it also keeps the listener on edge, unsure where it will go next. Vastly different from Suite para Violín y Piano is Enríquez’ work Ritual (1973). This intense piece is often dissonant, and uses a lot of extended techniques and alternative tuning. Enríquez also experimented with graphic notation, as seen below in the score for his piece Móvil II (1969-1972) for violin and magnetic tape. Enríquez created the tape at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center in 1972 by transforming and processing the violin’s sounds, and then the violinist performs live accompanied by the tape according to the directions written in graphic notation. A recording of Enríquez himself performing this piece can be heard in the listening section.

Graphic notation score for Móvil II

Enríquez was a tireless teacher and administrator, and he shaped much of the landscape of music education in Mexico. He served as the director of many Mexican music institutions and schools, including the International Forum of New Music, which now bears his name.

Enríquez is credited with bringing an international approach to music in Mexico, exposing a new generation of composers to European ideas about the avant-garde, serialism, aleatoric music, and extended techniques. Although his legacy in Mexico is well-established, his pedagogy and compositions deserve to be remembered throughout the world.

Listening:

Suite para Violín y Piano (1963), performed by Patricia Garcia Torres and Savva Latsanich:

Móvil II (1969-1972) for violin and magnetic tape, performed by Manuel Enríquez:

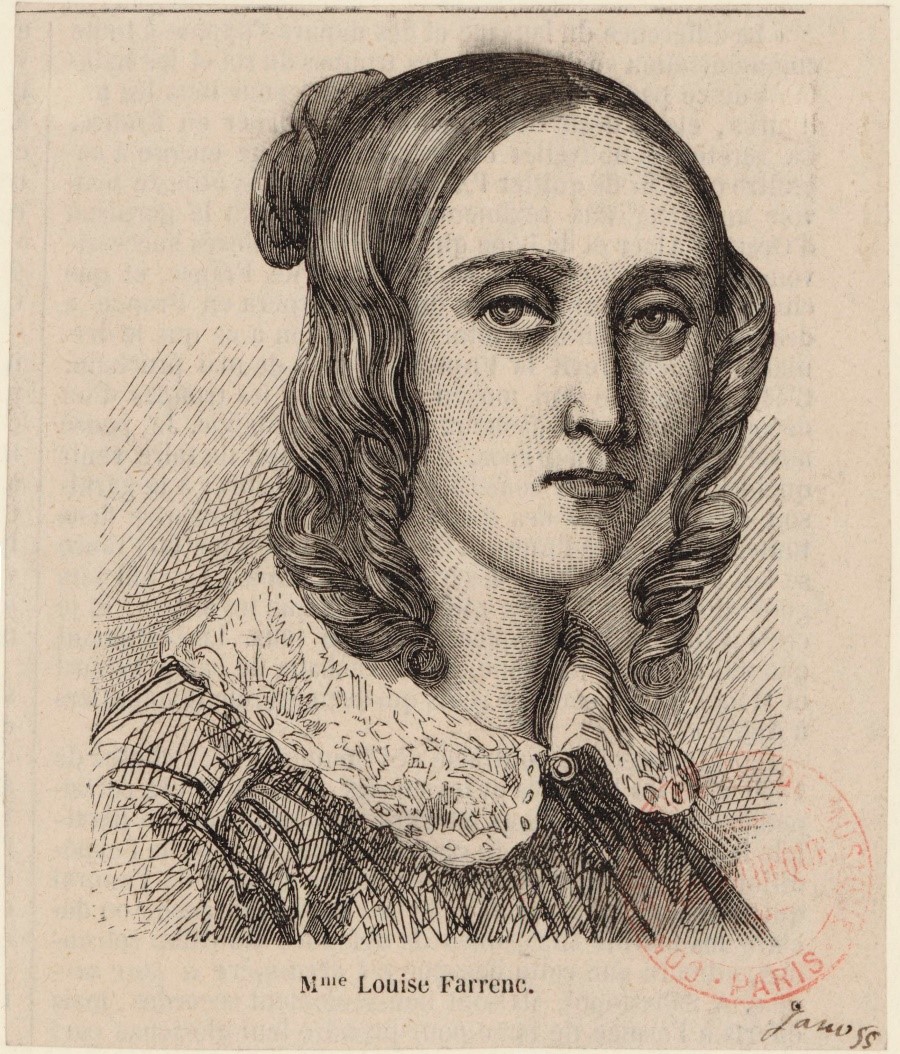

F is for: Louise Farrenc

There are few composers more fabulous, fantastic, and unfairly forgotten than our F composer – Louise Farrenc.

Louise Farrenc (1804-1875) was born into a well-to-do artistic family in Paris, descendant from a long line of famous sculptors on one side and, remarkably, female painters on the other. Farrenc began learning piano and music theory at the age of six, and went on to study with composer Johann Nepomuk Hummel. At age 15, Farrenc began receiving composition lessons at the Paris Conservatory from Anton Reicha.

While at the Paris Conservatory she met flutist Aristide Farrenc, who was a fellow student and ten years her senior, and they married in 1821 when Farrenc was only 17 years old. Aristide opened a publishing house, Éditions Farrenc, which became one of the foremost music publishers in France. It is partly thanks to Aristide for publishing and championing Louise’s works that her music survived, especially in a time when women found it prohibitively difficult to become published without the aid (or intellectual property theft, depending on your viewpoint) of the men in their lives, Clara Schumann and Fanny Mendelssohn being the most prominent examples.

One of Farrenc’s first pieces to gain widespread popularity was Overture No. 2, Op. 24 (1834), which was described by Berlioz as “orchestrated with a talent rare among women.” A few years later she was lauded for her set of solo piano variations, Air russe varié, Op. 17 (1835) by Robert Schumann, who wrote “Small, neat, succinct studies they are... so sure in outline, so logical in development - in a word, so finished - that one must fall under their charm, especially since a subtle air of romanticism hovers over them.”

As she became more established as a composer, Farrenc was able to edge her way into the almost entirely male musical scene in Paris. In 1842 she was appointed Professor of Piano at the Paris Conservatory, becoming the only female professor to hold a permanent and prominent position there throughout the entire 19th century. During her 30-year tenure at the Paris Conservatory she struggled to receive the same pay as her male colleagues, writing to the director of the school in 1850, saying “I dare hope, M. Director, that you will agree to fix my fees at the same level as these gentlemen, because … if I don't receive the same incentive they do, one might think that I have not invested all the zeal and diligence necessary to fulfill the task which has been entrusted to me.” While the administration did eventually cave to her request for equal pay, Farrenc was only ever allowed to teach female students and was prohibited from teaching composition because of her gender.

Farrenc was best known for her chamber music, and one of her most famous works is the Nonet in E flat, Op. 38 (1850) for flute, oboe, clarinet, horn, bassoon, violin, viola, cello, and bass. The premiere was led by the virtuoso violinist Joseph Joachim and “catapulted Farrenc to near-celebrity” status. In four distinctly different and gorgeous movements, Farrenc expertly lets each instrument weave and shine through the texture of the piece with its unique contribution.

Farrenc wrote three symphonies, and critic Maurice Bourges wrote that she was not only “the first of her sex to write symphonies, but one whose symphonies a great many male composers would be proud to have written." Symphony No. 3 in G Minor, Op. 36 (1849) was an instant hit with critics and audiences alike when it premiered, with one critic calling it “a strong and spirited work in which the brilliance of the melodies contends with the variety of the harmony."

After the tragic early death of her daughter at age 32 in 1859, Farrenc largely retired from performing and spent less time on composing, preferring to focus on teaching and scholarly pursuits. Lifelong admirers of early music, she and Aristide wrote an authoritative 23-volume set of books about performance practice of harpsichord and piano music called Le tresor des pianistes (The Treasures of Pianists).

Farrenc died on September 15, 1875, after a long career filled with many successes and many more setbacks. As Barney Sherman says in an article about female genius, “Farrenc … illustrates why gender balance matters for classical music. It's not because women compose differently than men … Rather, it's because excluding half the population means excluding half the genius. The long 19th century towers over classical music, but its legacy would tower more if women hadn’t been discouraged from adding to it.”

Listening:

Nonet in E flat, Op. 38 (1850), by Consortium Classicum:

Air russe varié, Op. 17 (1835), by Konstanze Eickhorst:

Overture No. 2, Op. 24 (1834), with the North German Radio Symphony, Hannover, conducted by Johannes Goritzki:

My thanks and appreciation to Southbank Sinfonia for supporting this project, and to Sam Olivier and Kate Walker for their gracious help in editing. Where I have quoted or used information from other people and publications, those sources can be found in the references.

Find out more about Antonia here

Check out a playlist of listening recommendations here:

Ambache, Diana. “Louise Farrenc (1804-1875).” Women of Note, Ambache.co.uk, www.ambache.co.uk/wFarrenc.htm.

AP. “William L. Dawson, Composer, 90.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 4 May 1990, www.nytimes.com/1990/05/04/obituaries/william-l-dawson-composer-90.html.

De la Vega, Aurelio. “Latin American Composers in the United States.” Latin American Music Review / Revista De Música Latinoamericana, vol. 1, no. 2, 1980, pp. 162–175. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/780307. Accessed 24 Sept. 2020.

Ellis, Katharine. “Female Pianists and Their Male Critics in Nineteenth-Century Paris.” Journal of the American Musicological Society, vol. 50, no. 2/3, 1997, pp. 353–385. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/831838. Accessed 24 Sept. 2020.

Enríquez, Manuel. “Manuel Enríquez, Móvil II, 1969-1972.” Fondation Langlois, www.fondation-langlois.org/html/e/media.php?NumObjet=16860.

Farra, Ricardo Dal. “Some Comments about Electroacoustic Music and Life in Latin America.” Leonardo Music Journal, vol. 4, 1994, pp. 93–94. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1513187. Accessed 24 Sept. 2020.

Friedland, Bea. “Louise Farrenc (1804-1875): Composer, Performer, Scholar.” The Musical Quarterly, vol. 60, no. 2, 1974, pp. 257–274. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/741636. Accessed 24 Sept. 2020.

Galván , Francisco Eduardo Barradas. “Contexts for Musical Modernism in Post-1945 Mexico: Federico Ibarra - A Case Study.” Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository, The University of Western Ontario , Western Graduate & Postdoctoral Studies, 29 Apr. 2019, core.ac.uk/download/pdf/215392584.pdf.

Heitmann, Christin, and Nicole-Denise Kadach. “Louise Farrenc (1804-1875).” New Historical Anthology of Music by Women, edited by James R Briscoe, vol. 1, Indiana University Press, 2004, pp. 170–187, https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=8vJu8gykYUEC&oi=fnd&pg=PA170&dq=louise+farrenc&ots=lqLrWUItoz&sig=zc3AktgB4BehabYlPDkNSzKLQ8Y&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=louise%20farrenc&f=false

Hoepfner, Fran. “Louise Farrenc's Defiant Third Symphony Ought To Cement Her Place In The Classical Canon: Classical Music Hour.” WQXR, Classical Music Hour, 7 Aug. 2019, www.wqxr.org/story/louise-farrencs-defiant-third-symphony-ought-cement-her-place-classical-canon/.

“History of the Tuskegee University Choir.” Tuskegee University, www.tuskegee.edu/student-life/join-a-student-organization/choir/choir-history.

Huizenga, Tom. “Someone Finally Remembered William Dawson's 'Negro Folk Symphony'.” NPR, NPR, 26 June 2020, www.npr.org/sections/deceptivecadence/2020/06/26/883011513/someone-finally-remembered-william-dawsons-negro-folk-symphony.

Jacobsen, Ryan. “Louise Farrenc: 1804-1875.” CU Scholar University Libraries, University of Colorado Boulder, University of Colorado, 30 Apr. 2020, https://scholar.colorado.edu/concern/graduate_thesis_or_dissertations/w9505124p.

“Louise Farrenc Biography.” Encyclopedia of World Biography, www.notablebiographies.com/supp/Supplement-Ca-Fi/Farrenc-Louise.html.

“Louise Farrenc.” Composers You Should Know: Louise Farrenc, Women's Philharmonic Advocacy, 2017, wophil.org/louise-farrenc-2/.

Manheim, James "Dawson, William Levi 1899–1990 ." Contemporary Black Biography. . Encyclopedia.com. 14 Jul. 2020 <https://www.encyclopedia.com>.

“Manuel Enriquez.” Manuel Enriquez (Biography), www.fondation-langlois.org/html/e/page.php?NumPage=1602.

Reich, Megan. “Black History Month: William Levi Dawson.” All Classical Portland, 22 Feb. 2018, www.allclassical.org/black-history-month-william-levi-dawson/.

Morris, Mark. “Mark Morris's Guide to Twentieth Century Composers - Mexico.” MusicWeb International, www.musicweb-international.com/Mark_Morris/Mexico.htm.

“Photo of Manuel Enríquez.” Orquesta Sinfonica Heredia Costa Rica , 4 May 2017, sinfonicadeheredia.com/2017/05/04/manuel-enriquez/.

Prieto, Carlos. “Manuel Enríquez - Compositor.” Música En México, 11 Aug. 2017, musicaenmexico.com.mx/musica-mexicana/manuel-enriquez/.

Raney, Carolyn. “Louise Farrenc.” College Music Symposium, vol. 21, no. 2, 1981, pp. 154–157. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40374114. Accessed 24 Sept. 2020.

Ruffin, Herbert G. “William Levi Dawson (1898-1990).” BlackPast, 23 Jan. 2007, www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/dawson-william-levi-1898-1990/.

Sherman, Barney. “Louise Farrenc & How Female Genius Can Flourish.” Classical Music with Barney Sherman, Iowa Public Radio, www.iowapublicradio.org/show/classical-music-with-barney-sherman/2015-09-04/in-1840-she-wrote-the-all-things-considered-theme-louise-farrenc-how-female-genius-can-flourish.

Slonimsky, Nicolas, et al. “Enriquez, Manuel, Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians.” Encyclopedia.com, Encyclopedia.com, 24 Sept. 2020, www.encyclopedia.com/arts/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-and-press-releases/enriquez-manuel.

Tello, Aurelio. “ Pytheas Center for Contemporary Music.” Manuel Enríquez (1926-1994), Pytheas Center for Contemporary Music, www.pytheasmusic.org/enriquez.html.

Tischhauser, Andreas P. “Louise Farrenc's Trio for Flute, Cello and Piano: A Critical Edition and Analysis.” Florida State University Libraries, Florida State University, Florida State University, 2005, purl.flvc.org/fsu/fd/FSU_migr_etd-1347.

Villegas, Victor. “Manuel Enríquez. Música Del México Moderno.” VicManMusic, Tiempo De Música y Universo, 17 June 2020, vicmanmusic.wordpress.com/2020/06/17/manuel-enriquez-musica-del-mexico-moderno/.

“William L. Dawson Biography.” Singers.com, www.singers.com/bio/2781.

“William Levi Dawson (1899-1990).” William Levi Dawson, African American Composer & Choral Director, AfriClassical.com, chevalierdesaintgeorges.homestead.com/Dawson.html.

“William Levi Dawson Biography.” Alabama Music Hall of Fame, www.alamhof.org/williamldawson.