double bass

I was considering a few options for my choice of movement but eventually decided on what I think is the most beautiful section from my favourite opera, Bizet’s Les pêcheurs de perles (Pearl Fishers). I want to work in an opera orchestra pit later in my career and have always loved the drama and excitement that a production can bring.

The opera is about two friends, Zurga, who is the mayor of a fishing village, and Nadir, his oldest friend, in Sri Lanka. The duet I have chosen comes after the two reminisce about how their friendship was threatened by their both being in love with the same woman, a priestess named Leïla. The words are the two promising that nothing shall come between them again, which foreshadows the rest of the plot.

One of the most amazing things about this whole opera is that at the time of writing, Bizet was 24 – the same age I am now. I find it incredible that someone so young and relatively inexperienced could have written such heartfelt, beautiful music. I was lucky to play in the pit at English National Opera for some of the rehearsals of their production of Les pêcheurs, and I will hold the memories of that dear for a very long time.

Find out more about Declan here

clarinet

Having grown up and studied music in Hungary, I often get asked about my experience of playing and performing Hungarian music. However, only recently have I been fortunate enough to gain more experience and insight into the Hungarian composer Bela Bartok’s trio called Contrasts, which I performed as part of my master’s degree in Hannover.

The final movement is most special to me and has moved me in ways that I could never have expected. The music is fast and exciting as if the players are chasing one another. And then, about halfway through the movement, a whole new world opens up. The piano gives a dance-like rhythm and the clarinet sets the scene with a song-like melody which is then taken over by the violin. In itself it’s pretty straight forward. The three instruments blend and melt together and, for a short while, dance with one another. Soon the piano returns even more violently to bring the mood back to its original fast pace.

At first we struggled with this rapid shift. It can be hard to change the mood so suddenly and for such a short period of time, before the music bursts out with energy again. Surprisingly, this slow section required a lot of our care and attention and it got me thinking about my own feeling. It made me realise that perhaps - in a very obvious way - in order to be able to set a calm and rich atmosphere, we have to start with ourselves. This may be clear to some but for me, this was one of those special experiences when we were able to move together as a group and change our emotions to benefit the music.

I found this experience deeply moving because we were able to put the music (initially the thing that brought us together as an ensemble) and our emotions in harmony. This experience has added vastly to myself as a musician and also as a person and I will always be grateful to have been able to perform it.

Find out more about Lily here

Administration Manager

The final movement of Mahler’s 10th Symphony is one of the very few pieces of music that will make me bawl my eyes out. The music is filled with the most excruciating tension and longing, with a heavy emotional subtext, so I don’t recommend listening to it with any sharp objects nearby.

The movement begins with a lonely tuba solo that’s rudely cut off several times by a military drum. There follows possibly the most tragically beautiful passage of music ever written – a simple flute solo accompanied by lower strings. It’s objectively beautiful in its composition, but there’s something about it that’s unquestionably sad too. (Gareth Davies, flautist of the London Symphony Orchestra, wrote a blog about this solo and how it changed his life; excerpts found here). The strings later pick up this melody and just as they’re about to reach the climax the military drum is back and strikes them into silence. It gives me the sense that Mahler is desperately trying to express something, convey an idea to his listeners, but just can’t quite get it out and it leaves a horrible sense of musical frustration.

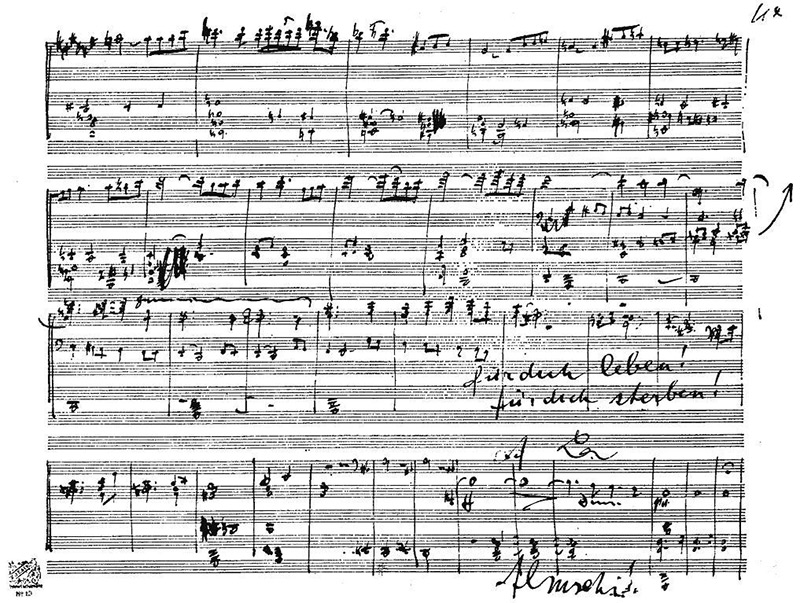

Perhaps the most famous and terrifying moment in the whole symphony occurs in the middle of this movement when the entire orchestra gathers on an earth-shattering triple forte 9-note clashing chord, which some people have dubbed the 'crisis' chord, as Mahler’s personal life was a complete mess while writing this piece, and this chord is basically an anguished human scream transcribed for orchestra. He was diagnosed with a serious heart condition (the ultimate cause of his death), and his wife Alma had cheated on him, and Mahler expressed his literal and romantic heartbreak not just through the music, but also in despairing comments, many addressed to his wife, scribbled directly onto the manuscripts of his sketches (see picture below). "für dich leben! für dich sterben!" (To live for you! To die for you!) and the exclamation "Almschi!", his pet name for Alma, scrawled underneath the final soaring phrase. This context adds an unbearable emotional weight to the piece for me, and it’s impossible not to shed a tear for poor old Gustav.

Extract from Mahler's Symphony No.10, final movement

I had the pleasure of seeing a live performance with the LSO under Simon Rattle in 2018. I said to my friend who was with me “Just a warning, I’ll probably cry in the last movement”. Ten minutes into the first movement and I was already soaked! Totally worth it though.

Find out more about Peter here

Cover image credit: Belinda Lawley